Stacy Kranitz

Life as Art | A conversation with photographer Stacy Kranitz

“The line between art and life should be kept as fluid, and perhaps indistinct, as possible".

-Allan Kaprow

This interview was conducted on December 20th, 2020 via Zoom.

Stacy Kranitz was born in Kentucky and currently lives in the Appalachian Mountains of eastern Tennessee. By acknowledging the limits of photographic representation, she makes images that create an expanded sense of authorship and accountability in which all parties (including the viewer) are complicit in the representational act as a false and yet, ultimately, satisfying and seductive construct. Her images do not tell the “truth” but are honest about their inherent shortcomings, and thus reclaim these failures (exoticism, ambiguity, fetishization) as sympathetic equivalents to more forcefully convey the complexity and instability of the lives, places, and moments they depict. In this way, her work acknowledges the failure of representation to ever be able to communicate the other.

Her work has been written about in the Columbia Journalism Review, British Journal of Photography, Journal of Appalachian Studies, Time, The Guardian, Juxtapoz and Liberation. Portfolios of her photographs have been featured in Granta, GUP, Harper’s, Hotshoe, the Intercept, Mother Jones, Oxford American, Photofile, Sewanee Review, Vice and the Virginia Quarterly Review.

Kranitz is a current Guggenheim Fellow (2020). Additional awards include Time Magazine Instagram Photographer of the Year (2015), the Michael P. Smith Fund for Documentary Photography Award (2017), and a We, Women grant (2020). Her work was shortlisted for the Louis Roederer Discovery Award (2019), and she has presented solo exhibitions of her photographs at the Diffusion Festival of Photography in Cardiff, Wales (2015) and the Rencontres d’Arles in Arles, France (2019). Her first monograph, As it Was Give(n) to Me, will be published by Twin Palms.

© Stacy Kranitz

Interview by Joaquín Palting

This year (2020) has been absolutely crazy for everybody. How has it played out for you, both personally and professionally?

I definitely feel fortunate so far, all of my loved ones are safe and healthy. It hasn’t changed my life that much because I live like a hermit. I used to live outside of town and only come in every 10 days or so. There’s not a lot to do in Smithville. We have 3 Dollar General Stores, a Walmart, a country bar and a strip club, so I’m not drawn to go into town that much. (laughter) I do travel a lot for work however, and I’ve been covering a lot of issues related to Covid. I sort of live an odd life where half of it I’m isolated, and I don’t even need a face mask because I’m in my bubble. Then I get thrown right into it for a couple days or a week when I get a photo assignment. Looking back 2019 was a difficult year for me and 2020 has been good. Because 2019 was so challenging, I am very sensitive to the fatalism everyone is feeling right now, and aware how quickly things can turn from being stable and good to being difficult and chaotic.

You completed your undergraduate degree at NYU, and you went to graduate school at UC Irvine. I always associate you with being from either LA or NY, but I was surprised to learn that you’re actually from Kentucky. Can you give us an overview of where you’ve lived? Do you consider yourself a southerner?

I grew up in the south, but I also grew up in Irvine California. Here’s the funny list of where I’ve lived. I was born in Frankfurt, Kentucky and when I was about a year old we moved to Nashville Tennessee, which is where my mom was born and raised. Nashville is really where I would’ve grown up. We had a family business there but we sold it when I was 5, and we moved to San Diego, then Coral Springs, Florida, and then from there on to Irvine, California. I feel like I grew up in Irvine though because those were my formative years, the adolescent/pre-adolescent years. It was only 5 years really but that’s the time where you develop your taste for music, culture, etc. It was all very southern California for me. I don’t speak like a southerner, I speak like a southern Californian. (laughter) Later in my life I lived in Oregon, then New York, and Los Angeles. Then I moved to Louisiana because I fell in love with a Cajun cock fighter, we lived on a bayou! Then I went back to New York, Irvine, and Baton Rouge. I lived out of my car for 3 years after graduate school, which made me go insane. Recently I bought a house in Smithville, Tennessee, and that’s where I live now.

Do you feel somewhat settled down in the Smithville?

Sometimes (pause), I am not sure why I am here really. I think what is nice is that I was able to buy a place for very little money. I used to have storage units all over the country. I would have piles of stuff in my car, which I would put in bags and then fly with those on the plane, and put them in different storage units across the country. It just got to be too much because I didn’t know what was where. Now I basically have a glorified storage unit! I live in this huge old home in the woods. I have this massive studio, which is wonderful, and the amount that I pay for my mortgage is nothing in comparison to what I would have paid in LA or New York. Now I’m free to travel and be a full-time artist, which has always been very important to me. I would never be able to do that in LA or New York.

Do you have family in Smithville, or did you just pick it randomly?

My friend Benjy Russell, who is also a photographer, lives here. Benjy has a cabin which I rented just after the period when I was living in my car. I kind of knew what I was getting into by living in Smithville, how remote it is, how little it has to offer, it’s a food desert, etc. My mom was born and raised here. I am a 6th generation Nashville, Tennessean, she’s 5th generation. My mom called someone in my family, her third cousin who’s my neighbor down the road. That cousin knew a realtor in town, which he is good friends with. That realtor helped me find a place out here. So to answer your question, yes! I do have family down the road.

© Stacy Kranitz

© Stacy Kranitz

As a kid did you have an interest in art and photography, or did you discover those things later in life?

When I was growing up there wasn’t a lot of our art in our house. We didn’t have any art books, and I didn’t have much exposure to culture. But, when I was 15 I went to a bookstore and this book caught my eye (Stacy holds up a massive dictionary sized book to show me). It was a Leni Riefensthal autobiography, which was in the bargin books section. (laughter) I was really blown away since she is obviously atrocious. She had gypsies pulled from Nazi concentration camps to be extras in her movies, and then had them put back in the camps.

She was totally complicit in a lot of bad things. There’s just no way around that fact. At the same time she is also this woman who lived 10,000 lives. She started off as a modern dancer, then she became a film star, and then she went on to make her own movies. She did all of these crazy fictional films that were so experimental. Then she becomes Hitler’s filmmaker, and she makes these films that are mind blowing. Then she reinvents herself again and again. Also, she takes a boyfriend that is 40 years younger than her. When she met Horst, he was 20 and she was 60. They stayed together until she died at the age of 101.

I had a complicated childhood, so I was really drawn to this dark character who reinvented herself over and over again. She constantly challenged the idea of who she was, and anything she set her mind to she would accomplish, and excel at. Then, she would just drop what she was doing and move on the next thing. That was really appealing to me, and that was my first exposure to the life of an artist. I’m still obsessed with Leni Riefenstahl. I also found it fascinating that she was so arrogant. There was something very appealing to me that she was so full of herself. I have low self esteem, which I get from my mom. I don’t come from a family of women who boast about themselves, and so I found that really mind blowing.

When did you decide to pick up a camera?

I got my first camera when I was 16. My grandmother had given me some money, like $100 or $150. I went to a used camera store and got an SLR camera. Something terrible, and old piece of shit Canon I think. Then I was off and running. I took my color film to a lab down the street. Also, my high school, University High, just down the road from UC Irvine, had a darkroom and I took a darkroom class there.

I actually wanted to be a filmmaker though because Leni Riefendtahl was a filmmaker. She was a photographer too later in life but really known for her filmmaking. Once I realized you had to work with people though, I didn’t want to be a filmmaker. (laughter) I just don’t work well with people, I’d much rather work alone.

After completing your undergraduate degree at NYU you became an editorial photographer. Once you had established yourself you decided to attend graduate school at UC Irvine. What motivated you to pursue an MFA?

I started working as an editorial photographer, and I was also shooting documentary projects on the side. But, I just wasn’t very satisfied with them. It’s not just that I was an editorial photographer, but I worked in photo journalism, which is even more creepy and more problematic. (laughter) Here I was doing what I thought was a very noble job, but I was becoming very disillusioned with it. Then I read, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, by James Agee and Walker Evens.

I was becoming really interested in this turn in the documentary tradition, and I started to make work that was challenging the subjective/objective relationship. Then a friend of mine told me that you could go to grad school for free. I had no idea! (laughter) I started researching it and I decided to go. Another factor was that it was 2008 and the economy had completely fallen apart. So it was a combination of all of those things: being disillusioned with my career, having been doing it long enough that I started to be given the same stories to shoot over and over again, and I said to myself, “this is it?” I thought to myself - this is not how I want to live my life.

In 2009, I started a graduate program in Louisiana but the program was too remedial. It felt like I was relearning things I had already learned as an undergraduate. So, I reapplied to programs that were more rigorous and began graduate school at UC Irvine in 2011.

Which schools did you apply to and why did you choose UC Irvine*?

UC Irvine, UCLA , USC, and University of New Mexico. I got into two of the programs and UC Irvine was more sophisticated than the other one, and also had better funding. After my experience in Louisiana, I wanted to go to a school where I felt like the dumbest person in the room.

I went to do a campus visit at UC Irvine and sat in on a crit class. I thought to myself, “oh man I am never going to be able to talk like these people.” All the students in the crit seemed to have come from UCLA, and they had a way of talking about art that I just wasn’t used to. After that experience I was sold though. Also, I didn’t want to get trapped in a hole by going to a photography specific program. I knew I would benefit from an interdisciplinary program far more.

*Disclosure: Stacy and Joaquín are both graduates of the UC Irvine MFA Program in Studio Art.

© Stacy Kranitz

© Stacy Kranitz

The idea of representation in photography helps define your practice. You describe your work as making “photographs that acknowledge the limits of representation.” Can you elaborate on that a little bit?

I’m interested in work that comments on the act of representation, and the ways that it fails to represent reality while pretending that it faithfully is. The disjointedness of that is really beautiful and disturbing to me, and it’s the point of departure for all of my work.

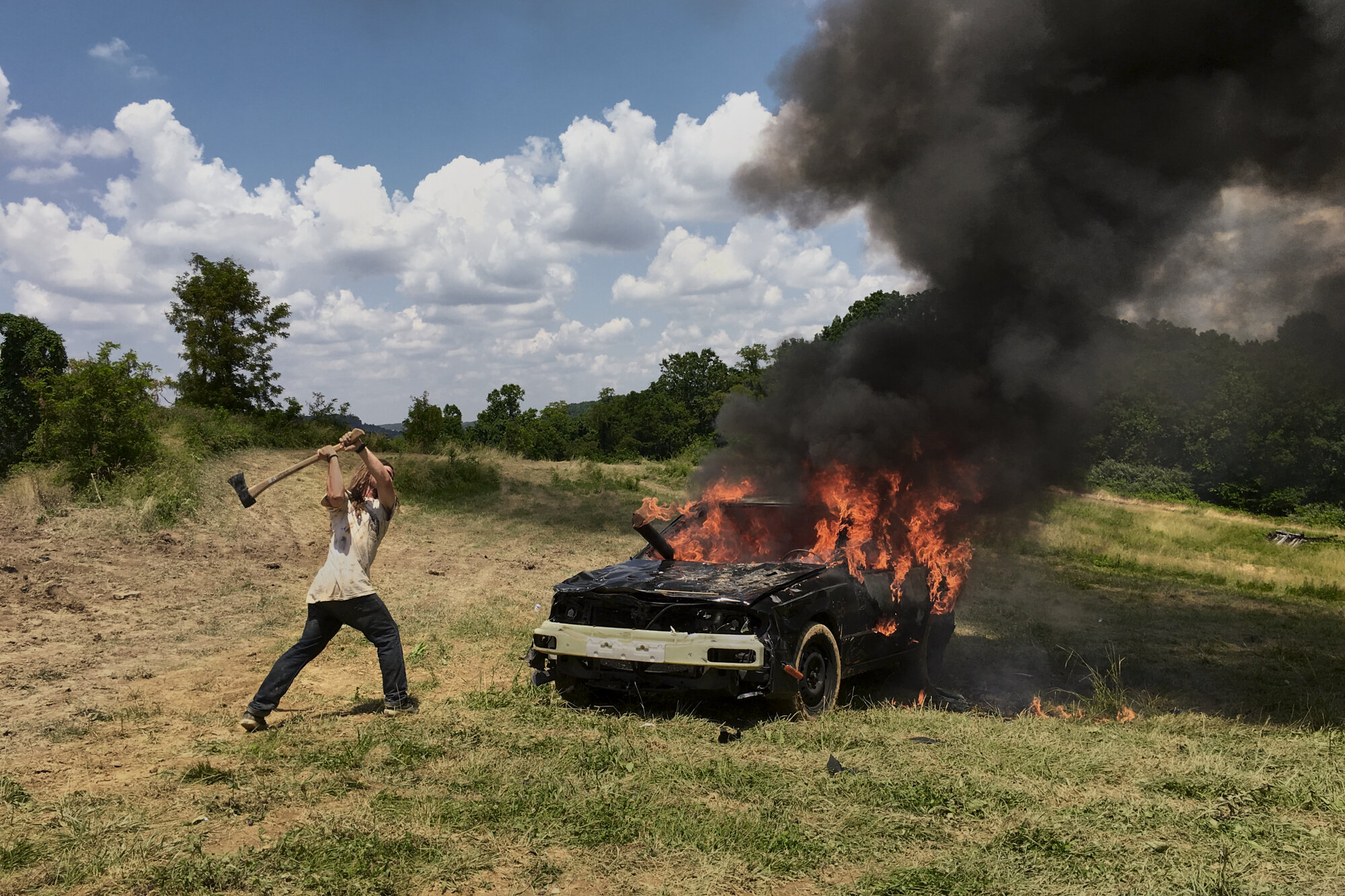

In your project, From The Study On Post Pubescent Manhood, you explore the unbridled youth and energy of skateboarders. What piqued your interest in looking closer at that subculture?

This is part of the work that I have done that documents violence as catharsis. I was very interested in this specific place (Skatopia**). It’s a place where poor behavior is happening, and so I wanted to document that. I was trying to see whether or not it is cathartic when people behave violently.

** Skatopia is an 88-acre skatepark near Rutland, Ohio owned and operated by pro skater Brewce Martin. Skatopia is known for its anarchist atmosphere and annual music festivals “Bowl Bash” and “Backwoods Blowout.” It was described by one writer as "a demented mess that meets halfway between an anarchistic Mad Maxian Thunderdome and a utopian skateboard society.” (Description from Wikipedia).

I’m a skater so I am very familiar with the social dynamics of the subculture. It’s a very male dominated space so did spending time with a bunch of skaters help define what masculinity is to you, or maybe ruin it? (laughter)

I was getting older when I started that project, so it was a really fun thing to be around young sweaty boys. (laughter) I loved it and I loved sexualizing them, the cameras ability to fetishize is really powerful. I was traveling a lot and making work, and I was used to being sexualized because of traveling alone. I wear short dresses. I don’t behave in a sexual way but I sometimes dress in a way that might make it seem like I want attention. That aspect sort of worked its way into the project.

I made a lot of really strong bonds in this project that weren’t like the bonds that I have with my other male friends. I was more of these guys mom’s age but also a social scientist and a documentarian. I was their friend and I would smoke pot with them, so I was this weird character in their lives. I had a very front row seat to their coming of age. These are guys that I’ve known now for 11 years.

So are you still working with some of them?

Yes! I started this project in 2009. I still go to Skatopia, and I am still close with around 5 of the guys I met there.

Did the idea of the female gaze come to mind while you were making these photographs? Like maybe this was an opportunity to flip the idea of the male gaze on its head?

No I was only interested in the idea of violence as catharsis. I grew up in a violent home so I have always been drawn to violence. What I was attracted to were these kids - their disenfranchisement, and feelings of frustration. A lot of these kids grew up with parents who were addicted to opioids, and so they were struggling against society and what they had been given; fucked up childhoods.

There is also an element of rural poverty in that region. So what is interesting to me is the need of these people to come to this place (Skatopia) to let out a darkness. That is really what this project was for me, and my own personal connection to that. I have taken people in my life to Skatopia over the years because it is a place that is very close to my heart. But, there are a lot of people who think that what goes on there is appalling and frightening. Everyone has a different relationship to that behavior, but to me it is this beautiful place where people can release their darkness.

Did spending time at Skatopia act as a catharsis for you from the violence that you grew up with?

I don’t know. It was a chance for me to see, and understand that there are people in this world, like me, who have a darkness in them and need a safe place to get it out. Whether that’s through therapy or whatever. I believe places like Skatopia serve a very important purpose.

© Stacy Kranitz

I am the son of a female photographer, and I am always interested in the different gendered experiences surrounding the making of photographic work. Do you consider it an advantage or disadvantage to be a woman working in the medium of photography?

I see it as an advantage for my documentary work, but I think it is somewhat disadvantageous for the editorial work that I do. I feel like sometimes people don’t take me as seriously. It’s not just my gender though it’s my stature. I’m 5’ 1” so that makes me really unthreatening, nobody is intimidated by me. I am also very goofy so I come off as very unassuming.

I can see how that translates to your documentary work because the people in your photographs always seem at ease. Whether you’ve spent 10 minutes making a portrait of a stranger, or it’s a person that you’ve known for years, it’s obvious that you have quickly established a rapport with them.

I think as photographers we always find the things that are helpful and we use those things. There are also things that are drawbacks but we just learn how to get around those.

Let’s talk a bit about your magnum opus, As It Was Give(n) To Me. You include yourself in some of the pictures. What about that part of the process is appealing to you?

I am very interested in the erasure of the distinction between my personal life and my professional life. I live and breathe my art, and that’s how I have always wanted it to be. The people that I have photographed over the years I consider to be as close as any of my other friends.

The idea of me inserting myself in the work though started with another project called, Target Unknown, and it was not something I thought I would ever do. I was there to photograph these WW II reenactments and there was something that just wasn’t working. They were photographs of people acting like Nazis, and it was falling flat in translation. Then I decided to “be” Leni Riefenstahl and it was subversive because I am Jewish, it was hilarious and so fucked up. I said “fuck it” I’m just going to get photographed dressed as Leni Riefenstahl.

I read in one of her biographies that Riefenstahl was called "the crevasse of the Reich" because she had taken up many lovers and it was rumored (although there is no definitive evidence) that she was having affairs with Hitler and Goebbels. So I decided to embrace the way Riefenstahl used her sexuality to get what she wanted, and I made out with some of the soldiers. It was ridiculous, and fun, totally bonkers. It also subverted the idea of these being fucked up people dressing and acing like Nazis because the photographer was doing it too. It became a way for me to give the project more depth. I thought to myself afterwards that I will never ever do that again, I just never wanted to put myself in the work again. It just seemed like an easy out, but then I did it again. (laughter)

So when was the next instance that it happened?

With the Appalachian work. I’m interested in this idea of truth being a collision between reality and my own fantasy of what the area is like. When I was a kid there was a miniseries called, Christie, on CBS. It was based on a romance novel, and I loved it so much. It was about a missionary who went into the smoky mountains to teach the children how to read and write, etc. Christie was so sure that she knew “right and wrong,” but then the mountain people show her that she had no idea of what was “right and wrong,” and everything unravels for her. I was really interested in photography’s relationship to colonialism, and I made the realization that the photojournalist is the contemporary missionary. I thought to myself, wow!, I’m a contemporary Christie. That collision though between the reality and my preconceived notion is the “truth”, and that’s why I wanted to be in these pictures. To illustrate the fantasy of objectivity.

© Stacy Kranitz

Why did Appalachia become an area of interest for you?

It was all from road trips that I had taken to Skatopia, because it’s in Appalachia. It was right when I was starting graduate school as well, so I thought it would be a great place to explore over the summer. I spent the whole first summer just driving and photographing, then when I got back to school I took some time to think about this as being a project.

I did a lot of research about the history of photography of the region, and also the history of the region itself. It just sort of fell in my lap and was perfect. Since I have such an interest in the documentary tradition it was interesting for me to realize how much harm photography had done to that region. Because of this history, it was an ideal place to make work that reflects on the failures of the documentary tradition.

I know that over the years there has been some pushback on this project.

That all stemmed from an interview that I had done with CNN when I first started it. I had given them a whole bunch of images to choose from, and they of course they chose the most problematic ones. They asked me in the interview, “does this represent everyday life in Appalachia?”, and I said, “absolutely not! It’s my own fetishization of the place.” But, they of course ran with the headline “Everyday Life in Appalachia” coupled with pictures that I took at a KKK cross burning, and of a snake handler. They set me up. They took a bait and click approach to the story. Still I had to take full responsibility, and people had a right to be angry.

That’s really sad because the entire situation was completely beyond your control. It’s horrifying to hear how they edited that piece. What’s strange to me is that they put the story together with the more sensationalistic images, because when you look at the whole body of work it is so much more than that. The pictures have an amazing rhythm and they include a wide range of things: portraits, landscapes, historical illustrations, drawings, pressed flowers, etc.

I feel like people are allowed to be upset with me, and people are allowed to be upset with the work. I think about the extraction of the coal from the earth, and the extraction of the mythology of the people. I believe that their feelings may not be entirely directed at me, and I give them the benefit of the doubt. People are frustrated with the way that documentary photography has portrayed the region. That was the lesson that I learned from the experience is that I have to be OK with that.

There are people who believe that the only way to offset the harm that has been done to the area, from a photographic standpoint, is to only make work that portrays Appalachia in a positive light. I clearly don’t abide by that, so the pushback isn’t a surprise. Since the book is about to come out I am really trying to prepare myself for the criticism that will inevitably come.

Yes, congratulations! the work from, As It Was Give(n) To Me, will be published by Twin Palms in early 2021. When can we expect to see copies?

If all goes well we will be going to press at the end of January, so maybe February. I am right in the thick of production at the moment. I am working on my files, making them look good. I am pulling the book apart, and putting it back together. It’s going to be big, about 300 pages. We started working on this book in 2015, so this has been a long slow process.

I am very nervous because after it comes out you can’t make any changes. Of course you’re going to immediately find something that you don’t like and then you have to live with it. So, I am going to anticipate that will be the case, and I am going try to put my best foot forward. (laughter)

I can’t wait to see it! Since it’s 300 pages I am assuming it will include some writing?

Yes! There are no essays, I didn’t want to go that route. But, the text that you see in the work (online), there is an extensive amount of that running through the whole book. The text takes a much more prominent role in the project. That was something that the publisher was really interested in so we worked through that.

It sounds amazing! Was the publisher very involved in the sequencing and other aspects of the design? Has it been a collaborative process or is this pretty close to your original vision for the project?

It’s pretty faithful to what I had come up with. I did a residency where I put the whole project together. Originally it was 500 pages, and then we slowly narrowed it down. He helped me take out things that just weren’t working. The big thing that he did, that was really interesting, is that he included the Post Pubescent work.

As a separate insert?

As it’s own chapter called Mutiny. It really works well, and I think it’s a brilliant idea.

© Stacy Kranitz

I mentioned earlier that, As It Was Give(n) To Me, includes pressed flowers. Why did they become part of the narrative?

That came about because I was depressed that I couldn’t take pictures. I was living out of my car, literally leaving the day that school would let out for the summer, and then coming back the day before it started up. It would be 4 months in my car, and you can’t stay in your car in the middle of the day because it’s too hot in the summer. I was thinking of things I could do because sometimes I would not want to talk with people. So, I started pressing flowers. In a way it replicates the process of photography because you are preserving something that is real. It’s also very relaxing, and I think it serves as a travelogue and references the specimen collecting that was common in colonial travel narrative.

Congratulations on your other big success this year, you were awarded a Guggenheim. Will the award be used to publish this book?

No. The book was too big when I first put it together, and I had to remove an entire chapter. That was really painful for me to take it out. But, I turned that chapter into its own project and that was the basis of my Guggenheim proposal.

So it will be a completely separate monograph?

Yes. I already have a publisher lined up so I’m in the process of putting that together as well. It will come out a year following the Twin Palms publication.

Was getting a Guggenheim always a professional goal of yours?

I never thought I would receive a Guggenheim. As an artist I only have a handful of ways to make an income. Print sales and editorial assignment work are my primary sources of income. I realized I needed to try to bring in more financial support from other places, and so I started to take grant writing more seriously. I spent a lot of time last year writing. Everyday from 8:00am - 12:00pm I would sit down and write. I never thought I was that good at writing, but now I feel I have gotten to a place where I am OK at it. I also started thinking about my age. I heard a lot of people apply for the Guggenheim for 8-10 years before they get one. So it seemed like a good idea to start applying.

© Stacy Kranitz

Who are some contemporary photographers that you find inspiring?

My friend Benjy Russell for a start, I think his work is incredible. Also, Taryn Simon, Leigh Ledare, and Carrie Mae Weems. I think the way she puts herself in her work is incredible. Alejandro Cartageña is really interesting as well.

Being a photographer can be somewhat isolating. Do you like to engage with a broader community of photographers.

I participate in a crit group made up of incredible women. There are also some other photographers that I have regular conversations with. I also like to mentor photographers. Sometimes random people will send me emails about that. If they are women I will do it. I enjoy mentoring emerging female photographers.

Are you a music fan?

I never in my whole life listened to pop music until this year. That’s been fun because I didn’t know that I would ever like it.

You mean top 40?

I mean people like Kesha, Beyoncé, and I love Taylor Swift! So pop music that empowers women. I also love country, I love soul, and metal.

Country!? What kind of country do you like?

Well some pop country, but also older stuff, and outlaw country, and of course Dolly! But my Kentucky boys that I really like are Jim Ford, Sturgill Simpson, and Tyler Childers. I’m obsessed with all three of them. I drive so much for work that music is really helpful.

You’ve logged a lot of miles out on the road. What is the craziest thing that you’ve seen or done?

One time I had an editorial assignment from Mother Jones to follow cops who were doing meth busts. The cops impounded this car, more specifically a “holler rocket”, which is a souped up car with a crazy sound system. The cops impounded 3 of these cars while we were there, and they didn’t have enough people to drive them all back, so they had me drive one.

I remember the car had these lights rigged to put on a light show when I played music. Like a private disco in the car. I was blasting the music and I'm driving back to the police station and I realize that I can go as fast as I want because the cops are not going to arrest me for speeding. So I pass the cops driving 95mph and waved as I passed. The cops seemed to think I was pretty cool for speeding past them in the Disco Holler Rocket. (laughter)

--

You can learn more about Stacy, and see her work, at https://www.stacykranitz.com

© Stacy Kranitz