Rebecca Norris Webb

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Originally a poet, Rebecca Norris Webb often interweaves her text and photographs in her books, most notably with her monograph My Dakota—an elegy for her brother who died unexpectedly—with a solo exhibition of the work at The Cleveland Museum of Art, summer 2015. She has published eight photography books, including the collaborative books Memory City (Radius Books, 2014) and Violet Isle: A Duet of Photographs from Cuba (Radius Books, 2009), both with Alex Webb; the latter exhibited at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Her photographs have appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine, and Le Monde among other publications. A 2019 NEA grant recipient, Norris Webb has work in numerous collections, including the MFA, Boston; The Cleveland Museum of Art; and the George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY.

ABOUT THE BOOK

Studying at the International Center of Photography in New York, Rebecca Norris Webb first came across W. Eugene Smith’s “Country Doctor,” his famous Life Magazine photo essay. She was immediately drawn to the subject of Smith’s essay, Dr. Ernest Ceriani, a Colorado country doctor who was just a few years older than her father. She wondered: How would a woman tell this story, especially if she happened to be the doctor’s daughter? In light of this, for the past six years Norris Webb has retraced the route of her 99-year-old father’s house calls through Rush County, Indiana, the rural county where they both were born. Following his work rhythms, she photographed often at night and in the early morning, when many people arrive into the world—her father delivered some one thousand babies—and when many people leave it. Accompanying the photographs, lyrical text pieces addressed to her father create a series of handwritten letters told at a slant. Ultimately, Night Calls is a meditation on fathers and daughters, on memory and one’s first landscape, on caretaking of the land and its inhabitants, and on history that divides us as much as heals us.

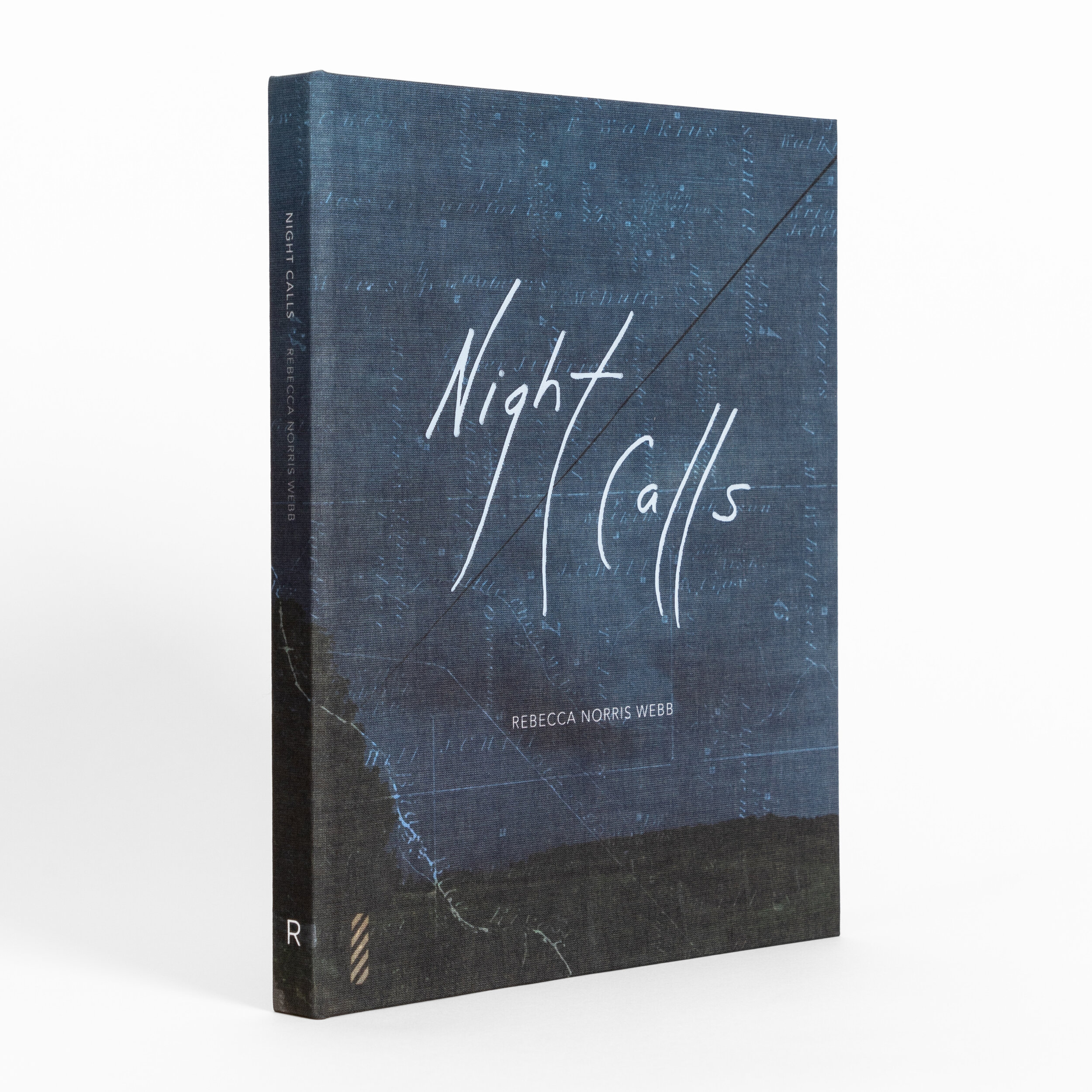

Rebecca Norris Webb, Night Calls Book Cover, Photo Courtesy of Radius Books

Interview by Dana Stirling

There is a sense of life and death in the work, I think. It starts with the profession of your father, delivering babies into the world. There is a sense of beginnings and endings – this notion of circle of life and its fragility. For every beginning there is an end, and it’s represented in your photography and in its sometimes-melancholic atmosphere, its use of still life and landscape.

Yes, there’s a bittersweet quality to beginnings and endings. In fact, my father was born at the tail end of another pandemic, the Spanish flu, which claimed some 675,000 lives in the US alone. There’s something hopeful, yet achingly vulnerable, about pandemic babies, coming into life amid so much death. Hard to believe that this same pandemic baby, my father, recently turned 101, celebrating his birthday quietly and safely at home with my mother, now 94, during this pandemic a century later.

You encounter former patients of your father, people whom he had delivered as newborns and people in the community. How was that experience? Were you surprised by any of these encounters? Did you learn anything new?

Listening to Dad’s former patients, I was particularly moved by Paul Davis’ story about his daughter, Carol Jenkins-Davis. The story reminds me that some wounds can pierce an entire community. On September 16, 1968, the 21-year-old Carol was selling encyclopedias door-to-door in Martinsville, Indiana, which was then called a “sundown town,” a community considered unsafe for Blacks to visit after dark. In this neighboring Indiana county, Carol was stabbed to death with a screwdriver because of the color of her skin.

Some fifty years after Carol’s murder, I made a collaborative portrait with Paul in his Rushville home. It was the day a nearby park had been rededicated to his daughter’s memory, in hopes of educating, healing, and ensuring Carol’s name would not be forgotten. A devout Methodist, Paul’s thoughtful and kind presence filled his sitting room, although he, like my father, was a man of few words. Decades of his quiet persistence — fueled by his love for his daughter and his unflagging faith — helped to bring Carol’s killer to justice. Six months after my visit, Paul died peacefully at home surrounded by his family. The accomplice of Carol’s killer remains unknown.

At 12 years old, I remember exactly where I was — perhaps like many in Rush County — when I learned about Carol’s murder, a memory forever entangled in the burnt yellow leaves of the bur oak outside my window. Over the past five decades, I wonder how many of us Americans in rural and urban counties have shared a similar communal wound — and its accompanying horror and ache, fear and anger —of the loss of a neighbor or friend or classmate or relative or workmate to a brutal hate crime. And can these wounds, I wonder, ever be fully healed?

Rebecca Norris Webb, Wasp, 2017

Rebecca Norris Webb, Paul, 2017

The book is accompanied with handwritten texts which are addressing your father, almost like a diary or a letter written directly to him. We as readers are merely observing your correspondence. Can you talk about the process of writing these texts? Why did you choose to write them in such a way and have their visuals represented in this manner? I found the pencil to be a really interesting choice and would love to hear more about it.

Originally a poet, my books are often influenced by poetic forms. Night Calls is no exception. Once I realized that it made sense to address the text pieces to my father — so Dad became the “you” of the pieces — I immediately thought of epistolary poems. Unlike actual letters, the letter poem is meant to be overheard by a third person, a future reader. Handwritten in pencil, these epistolary pieces echo the kind of “longhand” letters I’d penned to family and friends as a child. It also visually referenced my father’s handwritten patients logs from the 1950’s and 1960’s, in which he recorded each office visit and house call. Twenty years of these bound analog records were my guides while working on Night Calls. In addition, David Chickey, the book’s designer, used two pages from these patient logs as the book’s endpapers.

Perhaps fittingly, Night Calls’ readers have been sending me letters, emails, and DM’s from around the world in response to the book. It’s heartening to hear from so many that Night Calls has struck a chord, since we bookmakers often feel we’re working in the dark. One fellow photographer emailed that Night Calls helped her through this pandemic. She wrote that she’d been particular drawn to my text piece about the “secret room” in our Quaker family’s farmhouse, which had been used to hide runaway slaves before the American Civil War, as well as the phrase “I look like you.” For she, too — she wrote to me — resembles her father, who hid in a secret room during WWII to escape the Gestapo.

Rebecca Norris Webb, Eggs, 2017, Book Spread, Photo Courtesy of Radius Books

After 6 years of photographing, when it came down to editing the book, what was your main guiding lines? How did you select and edit the images, and what made some images not make the “cut”?

I work intuitively while selecting and sequencing the images of a book. I guess it’s my way of trying to channel the same intuitive mindset that made the photographs in the first place. Editing a book intuitively is about listening closely to one’s images to try to discern the rhythm of each book. With Night Calls, I realized that the flow of the book is meandering, as it passes from the distant past to the recent past to the present, from early morning to dusk to evening, from fog to thunderstorms to cloudless afternoons. So, fittingly, to punctuate the book’s meandering sequence, I used four vertical photographs of sycamores, those riparian trees that thrive on the banks of the Big Blue River, which flows past the farmhouse where Dad grew up and where four generations of our Quaker family also lived. Additionally, the sycamores’ mottled bark reminded me of Dad’s freckled skin. So, in essence, this quartet of sycamores became a metaphor for my father.

Rebecca Norris Webb, Float, 2015

Rebecca Norris Webb, Fog, 2015

This book is very much about memories and how we perceive them. How do you find photography to be a tool for such an elusive subject matter in your work?

For me, the project broke open emotionally and creatively for me when I decided to echo my father’s work rhythms, photographing often in the dark, when many of us come into the world — my father delivered some thousand babies —and when many of us leave it. Driving half-asleep in the dead of night or early morning, I’d occasionally be surprised by an image glimpsed slantwise — like “Float,” the surreal cloud reflection on my car’s window near Blue River Road — an image that sometimes would spark a memory. For me, memories — like the first lines of poems — often come to me from the side, unexpectedly.

Working collaboratively with Dad on Night Calls, memories often resurfaced for one or both of us — often fragments of a scene glimpsed from our two perspectives. For instance, my father reminded me about my first chest X-ray. I was a skinny, sickly kid with weak lungs, and Dad had grown concerned about my nagging cough during the flu pandemic of the late 1950’s. I don’t recall his blue eyes — which probably held a mix of alarm, caring, and perhaps even guilt that he hadn’t brought me sooner to the hospital. Pressed uncomfortably against the cold machine, I only remember catching a glimpse of Dad’s half smile above me, and hearing his gently joking voice, “Smile for the camera.”

Rebecca Norris Webb, Blue River Road, 2017

Rebecca Norris Webb, Landscape with Frost, 2017

I think it is interesting to think about the book in connection to the time we are currently living in — a year of a pandemic that has challenged us all. Your book talks about a connection between people, community, health, things that have all been challenged this year. Do you see things a little differently? I am curious to know if this year has changed anything for you and your photography?

Yes, isn’t this the question we’re all wrestling with these days: How will the pandemic change us — as artists and as human beings?

For me, I’ve learned from my father the art of listening closely to the suffering of others—and of seeing deeply. And isn’t this the shared territory of medicine and poetry — and, at times, photography, too? After all, doesn’t “care” mean “close attention”? For isn’t looking closely at the world outside ourselves the common ground where healing can begin to take place, even in our deeply divided country?

Rebecca Norris Webb, Blossoming, 2019

Rebecca Norris Webb, Eleanor, 2019

Rebecca Norris Webb, Your Sycamore, 2019, Book Spread, Photo Courtesy of Radius Books