Harvey Stein

Harvey Stein has had a wide-ranging career as an engaged photographer working in the documentary tradition, utilizing the medium to create photographs that capture the spirit and vitality of the people and places he depicts. His prime focus is to relate to his fellow human beings in intense and close-up images.

Through enduring documentary investigations of groups as varied as identical twins, Coney Island people, the street life of Harlem, artists in their studios, people living with AIDS, and life and death in Mexico, his projects have resulted in compelling and evocative in-depth photobooks that help illuminate the human condition and reveal his commitment to building connections through photography.

Among Stein’s nine published books are Parallels: A Look at Twins (1978), Coney Island 40 Years (2011), and Mexico Between Life and Death (2018). Stein’s photographs are in over 60 museum and corporate collections; he has had 88 one-person exhibits. He currently teaches at the International Center of Photography in New York City and conducts workshops worldwide.

Visit Harvey Stein’s website to see more of his work.

©Harvey Stein 2020 (Book photography curtesy of Zatara Press)

Interview by Dana Stirling

Thank you, Harvey, for taking the time to talk to me about your work!

I first would love to hear a little about how you first started in photography? What made you pick up the camera and when did you realize it was your passion and art form?

I studied engineering in college at Carnegie Mellon University. But my favorite classes were in the Humanities, English Literature and the Arts. After graduating, I worked for Bethlehem Steel in Eastern Pennsylvania but didn’t like what I was doing. I started to paint, did ceramics and wrote a bit. But I wasn’t very successful at any of it. But I did have a creative urge and loved seeing art at galleries and museums. I picked up a camera and knew almost immediately that this is what I wanted to explore. I moved to New York City to attend Columbia University’s Graduate School of Business and earned an MBA degree. In New York, I took several photo classes (not at Columbia) in my spare time. I started to shoot in the streets Y and found it fascinating. I was hooked. I produced my first book, Parallels: A Look at Twins, while working full time, from 1972 to 1978. In January 1979, I quit my corporate job to become a full-time photographer. This was probably my best decision ever. In February, 1979 I went to the Mardi Gras for the first time, and the new book is one result of the trip, albeit delayed over 40 years.

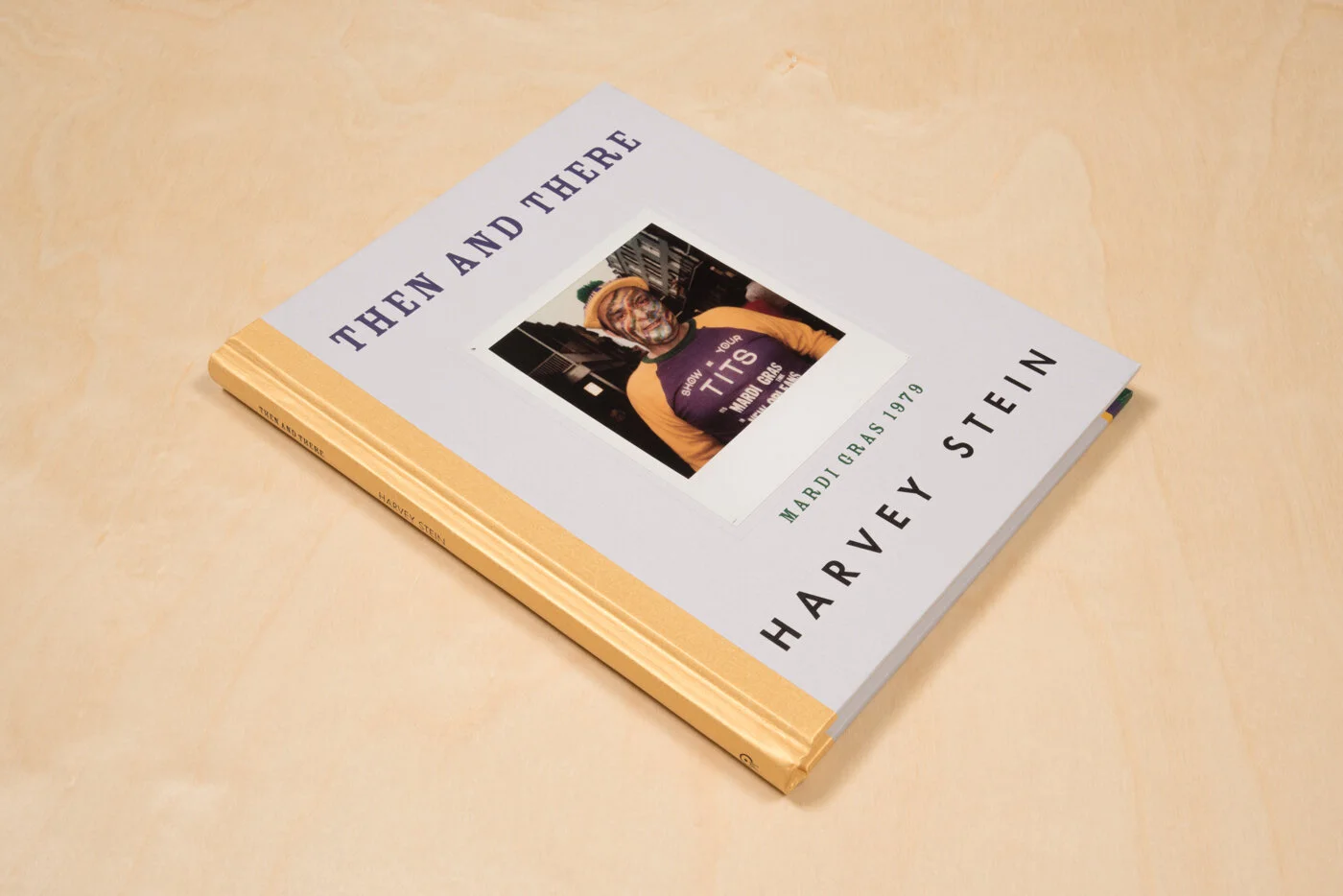

Your new monograph was just published by Zatara Press titled “Then and There: Mardi Gras 1979” featuring 47 polaroid portraits at the 1979 Mardi Gras in New Orleans. Can you tell us the decision to dedicate this book to this specific event and time? We often are accustomed to see books that represent a larger time frame, various events, while this book is so specific – it’s one event, one city in a specific year. The books capsulats this special moment of 1979 Mardi Gras. Can you tell us about this decision?

This is my ninth book. All the others took at least six years to shoot and produce. One book, Coney Island 40 Years, covers 40 years. In 2022, I will have a new book published, Coney Island People: 50 Years. “Then and There” is an anomaly, it was shot in one week. Wow, wouldn’t it be great if all my books could have been photographed that quickly!! There was never a concrete decision to record the special moments of 1979 Mardi Gras with the intent to do a book. I think what is special about the book is that indeed it is so specific and focused on one event, one city, one week. That is unusual. Also special is that it the photographs were made over 40 years ago.

I never planned to do a book of these Polaroids. I went to New Orleans to see, shoot and experience the Mardi Gras, mostly with my Leica M4’s. And that is what I did. Frankly, shooting with the Polaroid SX-70 camera was secondary. I used it in the early evenings with flash, probably since I didn’t have fast enough film for my Leicas to shoot in such low light.

©Harvey Stein 2020

©Harvey Stein 2020

When I looked at the images, they felt timeless actually – even though they are so specific in time, as mentioned above, but because they are so close up, it is hard to actually see much of a difference between us today and back in 1979. I think if it wasn’t for the polaroid, I don’t think I could have pinpointed when they were photographed. I can see their joy and their love for Mardi Gras, something I think could be found just as much today which I think it actually a really fun aspect of this book. I know this is an observation more than a question, but maybe you could give your thoughts on this notion?

I agree, it is not apparent when the photographs were taken. They could have been made this year at the Mardi Gras. Or at another exuberant event elsewhere. For me, a special aspect of the work is that the images are timeless. Or course, this is pleasing to me. I am amazed at how well the original images are preserved. Usually, some of the colors of Polaroids fade or change, not so with these prints.

Based on the above observation, there is a great text by Joanna Madloch [Montclair State University, New Jersey] at the end of the book and she writes “This is because the carnival happens beyond time and space. It occurs both now and never, as carnivalesque time is “time suspended” and it does not affect the “regular” chronological continuity. In this same way, the space of the carnival occupies a place located beyond the ordinary, and its narration does not carry on into everyday existence. In this sense the carnival is its own reality; a timeless utopia of abundance, pleasure, and play.” Which resonated with me and how I saw the book.

Joanna is a wonderful person and a brilliant writer and thinker. I met her in a class she took with me at the International Center of Photography and it was my great fortune to keep in touch with her. She sent me an amazing article of hers detailing the connection between photography and death. We discussed carnival and masks and she suggested that she write a short essay for the book. It’s a wonderful addition to the book.

©Harvey Stein 2020

©Harvey Stein 2020

Your images are so very close to these people – the distance between you and them is so small that in many cases you can barely see anything in the background besides the portrait. Can you tell us about the process of approaching these people and photographing them? Why did you want to be as close as you were while taking these photos? How was this small yet impactful human connection between you and them?

My photography practice is mostly on the street; I always try to make contact with the individual that I photograph. I am looking for connections between me, the subject, and the camera. I try not to shoot candidly on the streets, as most street photographers do. At the Mardi Gras, people in face paintings and costumes and makeup are exhibiting themselves in very creative ways. They want attention. I am in awe of the creativity and individuality of these people and show my enthusiasm to them, I show interest in them and I want to celebrate them. I usually just walk up to the subject, express my happiness at seeing them and ask to make a photo of them. I often give them a photo since the images with the Polaroid are relatively instant (the print takes about a minute to develop once out of the camera). This became part of the process, that of sharing and even taking another image to make it better. We became collaborators, so the human connection is what I am after and what I think makes for powerful photography.

By any chance do you have a favorite portrait in the book? If yes which one and can you tell us the story behind it?

I have many favorite photographs in the book but probably my most favorite is the image on the back cover, a woman in white face. Given that it was taken over 40 years ago, I don’t have any special memory of taking it, or for that matter, most of these images.

Out of curiosity – how many photos in total do you have from this 1979 Mardi Gras parade? How many did not make the final cut for the book?

I’d say I took 60 to 70 photos with the SX-70 camera. And really, I never photographed parades but rather the more casual street life of the Mardi Gras. This made it easy to approach people, with parades there are barriers and other obstructions. During the day, I only photographed with my Leica’s and probably took over 1000 images all told.

©Harvey Stein 2020 (Book photography curtesy of Zatara Press)

Let’s talk about the book itself – it has a very minimal, clean and straight forward design to it which works really well with the images. Can you let us in to some of your decisions in the book aesthetically and why were they important for you?

I give all the credit to Andrew Fedynak for the design of the book, he is the publisher of Zatara Press and also a terrific designer. I have several books on SX-70 photography, my work is in some of them, and I was inspired by them. I always wanted the full frame of the Polaroid to be shown, and given that the print is small, I always envisioned a small book. We picked the cover image since the man’s shirt, hat and face painting contains the colors of Mardi Gras-purple, gold and green. Andrew took those colors and added a gold leaf spine, and added the Mardi Gras colors on the back cover. Further, the front and back cover images are tipped in by hand, a slow and costly process. Since the images are minimal, we wanted a minimal design. I think it all works beautifully. It’s a compact and beautiful object as well as an interesting book.

You have published several books to date, all very different and unique in their approach. What do you think is most important in a photo book? How do you approach the editing, sequencing and overall design of the book? What are some of the biggest struggles you have faced in these processes?

What’s most important in doing a photo book are the photographs themselves and finding a theme that is coherent and strong. The images should be impactful and meaningful. I start editing and sequencing as soon as I have the notion to do a book. It’s a long and intriguing process. The struggles are to make the best photographs possible. It’s also a struggle to find publishers who believe in you and are not just thinking about the bottom line. And who don’t always want to cut costs to the detriment of the quality of the book. Andrew at Zatara is the best at understanding the artist/photographer’s point of view and not skimping on costs. Another struggle is to sell photo books, they tend to be expensive and the market is small.

At the end of the book you added a quote from Oscan Wilde “Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask, and he will tell you the truth.” I can completely see why you chose to use it – as it really captures the spirit of the work how people shift to their alternative self while wearing face paint and masks and are in a community of people who are like minded, expressive and creative individuals. I would love to hear your thoughts on this quote and how you feel it connects to you and the work.

I have always been intrigued by masks as art and face coverings that can transform us from our reality into an alternative, often much better reality and condition. I produced and published a small photo essay about people in masks in the 1970’s and my last book, Mexico Between Life and Death, contains many images with masks. I can’t recall where we found this quote, I think a friend sent it to me. It is perfect for the book. Masks give us a chance to become someone else, in both good and bad ways. And isn’t it ironic that during this year we are all implored to wear masks. Not to be political, but it’s very hard to understand why people are resisting them, they can help save our lives.

©Harvey Stein 2020

©Harvey Stein 2020

It feels that in almost all of your photo career you had focused on people, human interactions and the relationship of the portrait and the camera. It seems that you have an endless curiosity of people and how they live their lives around you. Can you tell us what pulls you in and drives you towards portrait photography?

I think the most challenging subject to photograph are strangers in the streets. Perhaps that is why I do it. It is also the most wide-ranging subject matter, there are 7.8 billion people on the planet that I consider possible subjects for my camera. They are endlessly divergent and interesting, all different and all the same. What can be more exciting and infuriating than humans? I even photographed Trump on the street, very closeup. Yikes. And rather than photographing scenes of people or crowds, I favor a one on one experience. I have made friends photographing individuals on the street. I married a woman who I met while photographing her in Central Park. I’ve never made an enemy photographing on the streets. I am interested in human nature and human behavior in public spaces, it’s what I am drawn to.

It’s now 41 years since this Mardi Gras of 1979. Do you think anything has changed since? Do you think photography or in particular portrait photography has changed? Would you have approached the same event in the same way in the year 2020?

Certainly, the world has changed markedly in the past 41 years. People have been born and have died during this time. Photography has gone digital. I am a dinosaur still shooting mostly film and making prints in a wet darkroom. But I would not have approached the 2020 Mardi Gras any differently. I would have looked for interesting and eccentric people to photograph closeup. The one difference: instead of shooting instant images with the SX-70 camera, I would have used my iPhone 11 to instantly record the great faces and energy of the participants.

©Harvey Stein 2020 (Book photography curtesy of Zatara Press)

©Harvey Stein 2020 (Book photography curtesy of Zatara Press)

I noticed that much of your work is actually Black and White and less color. This project was shot in color, which I can assume can be attributed to the colorful nature of the event, but can you talk about your choices of color vs BW? I think people sometimes forget that in film photography you make a decision of which esthetic path you are taking which sets the tone (no pun intended) for the project so you have to be mindful and intentional about decisions such as type of camera and type of film.

I’d estimate that 90% of all my photography is in black and white. I think b/w is personal, color can be pictorial. I believe that the subject matter is key in my work, and color can often compete with subject matter and even negate it. I see lots of color photography for color sake, this isn’t enough for me. Black and white more readily enhances subject matter, color not so. When I began photographing in the early 70’s, color wasn’t looked favorably upon by most street and documentary photographers. I think the date was 1974 when William Eggleston was the first person shown in color at the Museum of Modern Art here in NYC. It caused a stir and influenced a lot of photographers to shoot in color. My heroes were all b/w photographers, from Arbus to Winogrand and Friedlander. I grew up with b/w and still love the multiplicity of tones I can coax from b/w. This book is my second in color out of the nine books I’ve done so far. It can be attributed to two things: the colorful nature of the subject and the irrefutable fact that the only SX-70 film available was in color.

You’ve been what we could traditionally categorize as a street photographer for many years now. What would be your main advice for a young photographer?

My advice would be to photograph as often as possible, find strong and personal themes and work on long term projects. This will keep you engaged and passionate. Love what you are doing and always be curious, this might be the two secret ingredients.

©Harvey Stein 2020

©Harvey Stein 2020 (Book photography curtesy of Zatara Press)