Sarah Wilson

Sarah Wilson

DIG: Notes on Field and Family

Hardcover

11.25 x 9.25 inches

128 pages

Edition of 350

Yoffy Press

2023

About the Book:

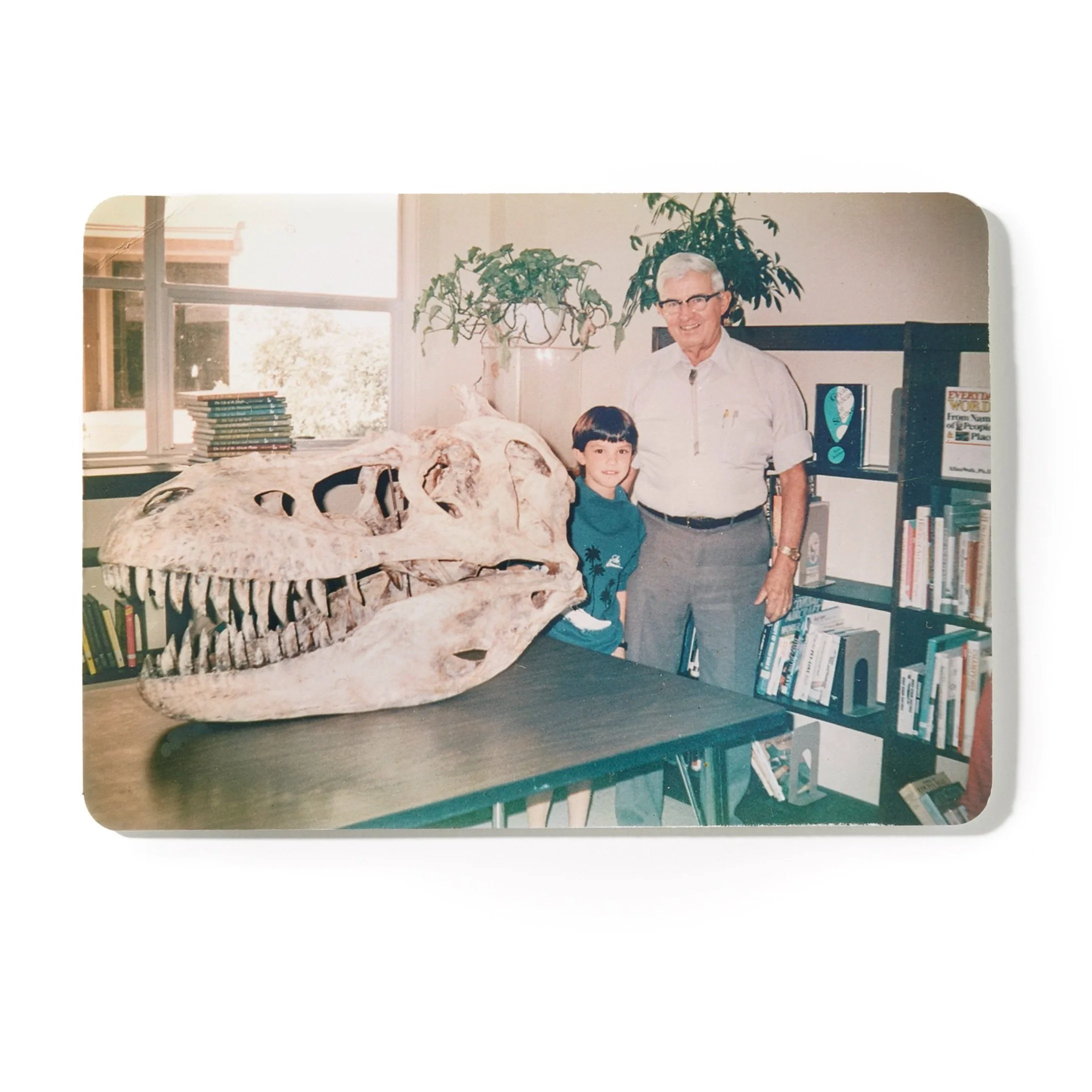

Before he died, photographer Sarah Wilson’s grandfather gave her three black metal boxes filled with faded Kodachromes. The images featured geologic charts, rock formations, bone fragments and skulls, and landscapes from his annual digs in West Texas and Big Bend National Park. These were his teaching slides from when he was a professor of geology and paleontology at the University of Texas. Holding them up to the light, Wilson realized that she and her grandfather photographed some of the exact same desert landscapes, from the same vantage points, only fifty years apart. This shared connection ignited an adventure and a long-term project, featured in the pages of her first book, DIG: Notes on Field and Family.

Wilson joins paleontologists on digs every winter in the Big Bend area, searching for bones and photographing the same stark desert landscapes featured in those vintage 35mm transparencies. But her work is not just an homage to her grandfather. She has created conceptual self-portraits in the style of geology and anatomy charts, combining the personal and the scientific. For Sarah, these annual digs are a pilgrimage to an origin story that reaches beyond traceable generations. Each bone collected is evidence of the slow, significant work of evolution, serving as a bracing reminder that we, as humans, sit at the very end of that timeline.

Book review by Max Cavitch |

Sarah Wilson’s West Texas landscapes are like snapshots of eternity. The photographs in her début photo book, DIG: Notes on Field and Family, include long vistas of mountains layered with pink sediment, ranging all the way to the horizon; valleys and desert basins carpeted with scrub- and grasslands and punctuated with large, spiny cacti that look like dinosaur snack-food; and ancient, rust-colored cliffs rising up to meet the pale permanence of blue-green sky. These are photographs of a terrain that bears visible traces of geologic time. As Wilson herself writes, “its rocky stretches speak of seismic moments. Floods and volcanic eruptions shaped this land where dinosaurs roamed and early mammals emerged” (p. 10).

Image by Sarah Wilson

Wilson’s majestic and largely unpopulated landscapes are interspersed throughout a book that is also a very human story. Specifically, it’s a granddaughter’s story about paleontologist John A. Wilson, who, when Sarah was a little girl, brought Cenozoic fossils to her elementary school for show-and-tell and who, at the age of 93, died while gazing at grown-up Sarah Wilson’s photograph of a bright green Ocotillo plant, taped to his hospital-room wall (pp. 28-29).

Image by Sarah Wilson

During his long career, John Wilson took countless photographs in and around this section of the Trans-Pecos known as Big Bend, and part of his legacy to his granddaughter was several boxes full of his old 35mm Kodachrome slides. They include pictures of landscapes, rock formations, excavation sites, fossils, his University of Texas lab, his colleagues, and various geological charts and depictions of ancient mammals, which he used in his lecture presentations. Looking through these slides after his death, Wilson writes, “I realized that my grandfather had photographed some of the exact same locations that I would photograph 50 years later” (p. 30).

Image by Sarah Wilson

Indeed, several of the book’s two-page spreads are diptychs, each featuring an enlargement of one of John Wilson’s Kodachromes and Sarah Wilson’s much more recent photograph of the same view from the same perspective: the breathtaking cliffs of Santa Elena Canyon (pp. 34-35); Nine Point Mesa seen across the Agua Fria Valley (pp. 36-37); the sinuous Rio Grande as it appears from Big Hill, along the Camino del Rio (pp. 38-39); and the volcanic peak of Goat Mountain (pp. 40-41). The topographic features in these paired images are so nearly identical they could almost have been shot on the same day, rather than decades apart. Yet the fading of the transparencies and the date-stamps visible on some of their cardboard borders work against this illusion of synchronicity. In another image, Wilson holds up her grandfather’s slide of a castellated rock formation so that it’s part of (rather than adjacent to) her own composition of the same view—creating the slightly uncanny juxtaposition of two skies separated by half a century, but seeming to share precisely the same hue, value, and saturation (pp. 92-93).

Image by Sarah Wilson

John Wilson spent his life digging things out of the ground—including the perfectly intact skull of an enigmatic 38-million-year-old primate known as Rooneyia viejaensis (p. 51). Sarah Wilson calls her book Dig not only as a metaphor for the excavation of her grandfather’s Kodachromes, but also because they inspire her to join some of his surviving colleagues on new digs and to search for more early primates like Rooneyia viejaensis. “Someone on the [first] trip found a rhino tooth,” she reports, and “someone else, a tapir jaw. Lots of 43-million-year-old rodent teeth, but no primates” (p. 58).

Image by Sarah Wilson

Wilson and her new associates dig up these ancient things and take them away to be cataloged and studied. But Wilson also adds something to this landscape of remnants: she scatters her grandfather’s ashes “amongst the fossils that have yet to be found” (p. 63). She also adds something special to the collection her grandfather started so long ago. On only her second dig, she finds a portion of the lower jawbone of a 43-million-year-old miniature-deer-like mammal known as Texadon—the first such specimen ever to be found, now archived with the name of its novice collector alongside the many fossils that bear her grandfather’s name.

Because of her commitment to documenting the ongoing work of UT-Austin’s Vertebrate Paleontology Collections, Wilson is appointed as their “first and only” Artist-in-Residence, which adds a further dimension to her identification with her grandfather. She even starts using his old camera, looking at the world as if through his eyes (pp. 86-87). Her residency also creates a link between her photographic “excavations” and the digs of her grandfather’s remaining colleagues, while giving her unfettered access to the vast collections themselves. A number of the book’s photographs are stylized compositions featuring some of its most impressive artifacts.

Image by Sarah Wilson

After spending so much time with “the endless shelves of specimens spanning the entire fossil record,” Wilson starts to feel what she calls “a unique connection to questions of Deep Time,” asking herself: “How and why did this dizzying timeline get started and where do I fit in to all of it?” (p. 82). She admits that such questions can be disorienting, which is why she appreciates the “grounding” effect of the precise, localized, patient work of the dig. At the end of the book, she also digs up some old black-and-white snapshots taken of and by her grandfather—some of them now almost a century old. They include a particularly striking picture of John Wilson as a very young man, taken in 1939 in Abiquiú, New Mexico, about an hour’s drive north of Santa Fe (p. 106). At that time—perhaps at the very moment this photo was taken—another artist, Georgia O’Keeffe, was also in Abiquiú (which would soon become her permanent home), painting northern New Mexico’s mountains, rivers, flowers…and bones. One can’t help wondering if they ever crossed paths.

Image by Sarah Wilson

Intersecting and diverging timelines—both human and geological—are given compelling visual and narrative form in DIG. It’s a photographer’s diary, a family chronicle, a celebration of science, an ode to West Texas, and a compendium of landscape, portrait, conceptual, and found photographs that shuttle back and forth between the time-bound and the timeless.