Eva Gjaltema

Eva Gjaltema

The First Three Years

Edition of 250

92 pages

Munken Lynx Rough

Swiss bound

Offset printed

2018

Self Published

From the artist:

The First Three Years is based on the artist’s personal experience of becoming a mother; on the contradictory nature of the event and the conflicting emotions it creates— the awe at the incredible ’once in a lifetime’ beauty of motherhood mixed with feelings of daunting powerlessness and isolation. We live in a time where women increasingly feel a great deal of stress— both self-imposed and external— to juggle all life roles perfectly: mother, artist, professional, companion.

Grab a copy of the book here

Book review by Charlotte Irwin |

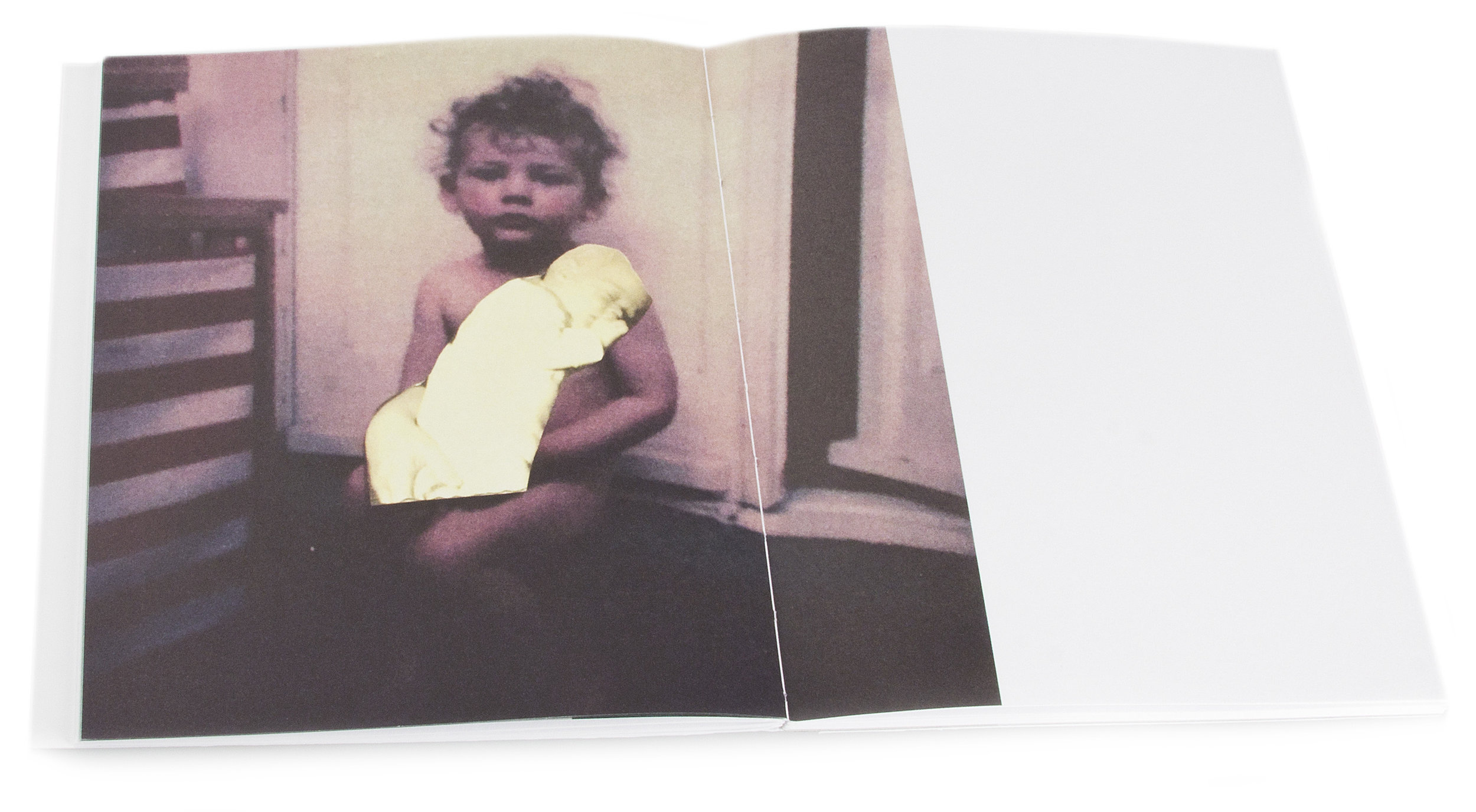

What first strikes me when I look at Eva Gjaltema’s The First Three Years, is how fitting the concertina folds, holding the sparse and muted images of her son’s development within this layered book, are. The images layer on top of each other but remain conjoined, just as our growing identities – new versions of us – bleed and fold into our experiences and selves of before. And perhaps this is no more pertinent than to a woman who has become a mother.

Gjaltema is not only charting her baby son’s early years, but offers up visual snippets of the peculiar “struggle” of motherhood. As the pages pile on top of one another, with images of her baby interspersed with those of the surroundings of their home, the book acts as an exploration of how motherhood destabilises a woman’s identity, and in this Gjaltema is explicit: “when she is with them she is not herself; when she is without them she is not herself”.

In that, it isn’t unexpected that there is a melancholy to the photographs that are far from the typical milestone snapshots we expect of childhood. There is no first smile, that time you put their clothes on back-to-front, or the first trip to nursery. Instead, we have blurred, almost dulled images of a baby lying awake in bed, a toddler at the table, the corners of bedrooms, a plant with trinkets hanging from its small branches, as Gjaltema seeks to find with a camera the scene of “the anarchy of nights the fog of days”.

At times, it feels like Gjaltema is presenting the aftermath of events that take place in the domestic confines of childhood, and that the quiet reality captured here tells only part of the story. And so, when the images give way to something more childlike and fantastical in the form of cut outs and collage, I welcome it.

Borrowed images allow Gjaltema to look to other mothers from history, where a cut out of a baby is pushed in a pram of a smiling mother from the past, and on another page a young boy holds the child while a woman seems to look on from the other side of the image. Yet melancholy seeps back in with the composition of a baby in an old-fashioned gown lying in the arms of an absent, cut-out mother.

This feels like the crux of it. The lack of the mother in this cut-out, and the absence of Gjaltema herself throughout the images of her son and home, create a sense of foreboding and still anxiety. I start to wonder about how the creation of this new person takes away from a woman, and what the presence of a mother actually consists of. Because what could be worse than an absent mother?

The woman behind the camera, the maker of this book, and the creator of this child is identified by the things she has created, but her identity is then subsumed by her domestic role. But I start to think that maybe the fact she’s not there to be seen, but is reflected in her creation, is not a complete loss but something more powerful. The death of the author in autobiography feels strange and self-denying, but in the case of motherhood it feels like a quietly beautiful act.

Grab a copy of the book here